The history of money in Montenegro not only depicts the turbulent history of the Balkans and the various influences and interests, but also the continuous striving of the Montenegrin people to be independent and to choose their own fate. Montenegro mostly used foreign currencies throughout its long history, these being Roman, Austro-Hungarian, Turkish, Venetian, and even the Napoleon (French gold coin) money.

The first idea for Montenegro’s own money came from the Bishop Petar Petrović

Njegoš in the 19th century. It is assumed that he got the idea of minting coins during his stay in Naples after meeting with Carl Rothschild, a banker and a financial magnate.

Under the influence of Rothschild, a cast for minting coins was purchased and brought to Cetinje, the Montenegrin capital at that time, in 1851. However, no evidence has been found that any coins were in fact minted, only a wax impression of a Perun coin, the currency named after the supreme Slavic deity, which is kept in Cetinje. His great wish to mint coins of Montenegro was later realized by King Nikola I Petrović.

Photo source: CBCG The cast for the golden Perun, 1851

Money in Montenegro since the beginning of the 20th century until World War I

The Austrian money, florin, was the main currency in Montenegro in the second half of the 19th century. At that time, Montenegro was an underdeveloped country with a dominant subsistence economy and the most intensive original accumulation of capital was acquired through trade. However, the development of the trade in goods and an increase of trading capital created a growing need for money.

Since a large number of foreign currencies had circulated at that time, like krone, talirs, napoleons, rubles, that system created numerous difficulties. Austrian money circulated without any compensation as if Montenegro were a part of Austria-Hungary. In the political and economic circumstances at that time, the functioning of foreign currency had a series of negative consequences. Consequently, at the end of the 19th century, Montenegro sought to issue its own currency.

By the Decree of Prince Nikola, on 11 April 1906, the Ministry of Finance was authorized to mint nickel and bronze coins in the amount of 200 000 krone. In the end, 209 000 krone were minted. Although the intention was that the coins should be minted in Paris and in Russian mints, they were ultimately minted in Vienna. Nickel and bronze coins were put into circulation on the 28th of August 1906.

However, due to the lack of small coins, Austrian money still remained in use in Montenegro. Therefore, a new issue of coins was minted in 1908 in the nominal amount of 110 000 krone. Besides krone, other currencies were also in circulation – the US dollar, sent to Montenegro by Montenegrin immigrants, and to a lesser extent, the British pound, the French franc, German mark, the Turkish lira and the Russian ruble. Under these conditions, the monetary sovereignty of Montenegro was limited.

Based on the initiative of the chief of the Ministry of Finance, M. Jovanović, the idea was to mint a new currency – the perper. With the purpose of completing the monetary system, the Law on State Money of the Kingdom of Montenegro was passed in December 1910 and it came into effect at the beginning of 1911. The law prescribed that Montenegro would adopt gold currency for monetary traffic in its territory and the monetary unit would be the perper.

20 Perper, 1910. Photo source: Kunker

The law prohibited circulation of foreign currencies in the territory of Montenegro, which was the main goal of this document. Counterfeit money soon appeared, in particular, counterfeit silver coins. In the newspaper “Glas Crnogorca”, the Minister of Finance gave a description of counterfeit money and how to recognize it.

As Montenegro was preparing for the First Balkan War, it had a significant negative effect on public finances. Therefore, the Law on issuing treasury notes was passed in 1912. Pursuant to this law, treasury bills were issued as Montenegro’s first paper money, which was guaranteed by the state up to their face value.

Treasury note worth one Perper, 1914. Photo source: numismondo.ne

The second issue of treasury notes was performed in 1914, while the last one occurred in December 1915. All issues had a limited circulation period.

Money in Montenegro from World War I until 1999

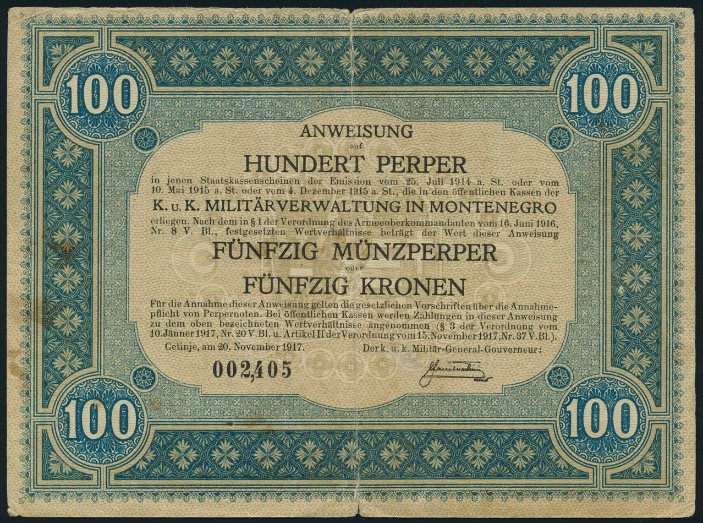

At the beginning of 1916, Austro-Hungary occupied Montenegro and assumed the governance of the monetary system. The disbursement of paper money was stopped but based on the decision of the occupying authorities it remained in circulation, however, an Austrian seal had to be imprinted on the money.

Treasury note worth 100 Perper, 1917. Photo source: Worbes Verlag

The perper disappeared from the scene when Montenegro joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1918, putting into circulation the dinar, a currency of the newly established state. Perper coins were exchanged at a rate of 1 dinar = 1 perper. Since no gold coins of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes existed in that period, it was more cost-effective for the holders of perper to negotiate the perpers for gold rather than exchange them for dinars. Since there were 17 675 734 perper banknotes in circulation, which was 3.06 times higher than perper coins, the exchange rate was 5 perper banknotes = 1 dinar banknote.

10 Dinars, 1920. Photo source: Old currency exchange

The National Bank of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes functioned as the central bank and it was renamed as the National Bank of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929.

After the disintegration of the SFRY, two former member republics – Montenegro and Serbia formed the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) on the 28th of April 1992. In the new country, the monetary system was re-centralized, wherein the National Bank of Montenegro (NBM) lost its autonomy and became a regional office of the National Bank of Yugoslavia headquartered in Belgrade.

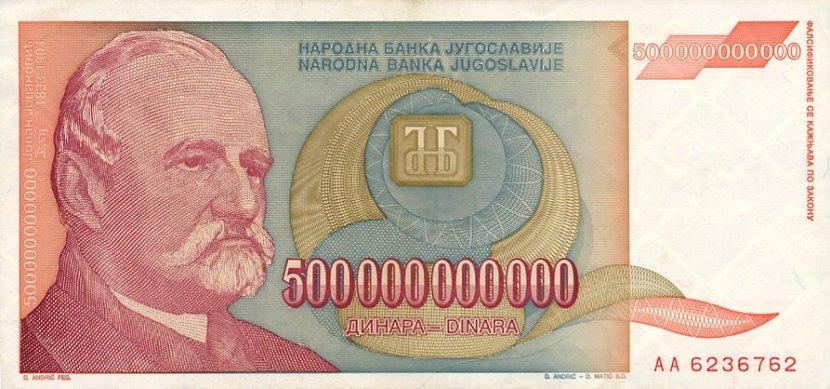

After the crash of the common market and simultaneous outbreaks of war in two former Yugoslav republics, the monthly inflation rate in Serbia and Montenegro was 50% in February 1992, reaching 100% in June that year. This percentage represents the general threshold that defines hyperinflation. At the end of 1993, inflation amounted to 3 508 091 786 746%, which represents some of the highest hyperinflation rates in the world.

500 billion Dinars, 1992. Photo source: mises.org

Abandoning the dinar and introducing the German mark and the euro

At the beginning of 1999 the Montenegrin government started looking for a way to establish monetary independence in Montenegro. Dual currency system consisting of the German mark and the dinar was introduced late in 1999.

The adoption of the mark as the republic’s sole currency was aimed in part at helping to bring Montenegro out of the shadow of its bigger partner, Serbia, and moving it closer to the West. For a transitional period of more than a year, the German mark and the dinar circulated together in Montenegro. The German marks that had circulated in informal channels started to enter the legal avenues. Therefore, it was estimated that a sufficient quantity of this currency was in circulation and there was no need to use the dinar as a currency anymore. Thus, the German mark (DEM) became the only legal tender from 2001 until March 2002 when the euro was introduced.

Since the euro is a global currency traded internationally and can be bought anywhere in the world, the European Central Bank cannot control such motions and cannot forbid the promotion of the use of the euro.

The adoption of the euro in Montenegro was motivated by both economic and political considerations. Montenegro has had a number of benefits since the introduction of the euro: price stability, return of the credibility of its monetary policy, faster development of financial systems, interruption of the fiscal deficit monetisation and substantial FDI inflows.

Of course, the adoption of the euro was not without cost. Most importantly, Montenegro lost its ability to pursue an independent monetary policy adapted to its own economic needs, rather than those of the Eurozone.

Currently, Montenegro is in the EU accession process and its objective is to address the issue of the unilateral use of the euro through negotiations with the EU and to become the Euro Area Member shortly after joining the EU.

Unlike official members of the Eurozone, Montenegro does not mint coins and therefore has no distinctive national design.

Sources: Central Bank of Montenegro, montenegrina.net, mondo.me, researchgate, Radio Free Europe, Beyond the EU